The Start of Noise

The odd story of how one woman and four men from England influenced Hip Hop, Techno, and Industrial music with a machine from Australia via Malcolm McLaren, Yes and Italian Futurists.

Zang Tumb Tuum’s house band had a pretty ignominious start in life, being born, primarily, out of boredom. Boredom mixed with a seemingly pompous, intellectual desire to confuse and confound, to maybe ‘out-Factory’ Tony Wilson. But little did Paul Morley and the other founding members of Art of Noise, Trevor Horn, Gary Langan, Anne Dudley (an RCM graduate) and JJ Jeczalik, realise that their grandiose, sometimes baffling and altogether pretentious project, based around the equally baffling Australian music computer, the Fairlight CMI, would serve as a driving force for not only electronic music but for the burgeoning Hip Hop scene, thousands of miles away in places like New York City’s South Bronx.

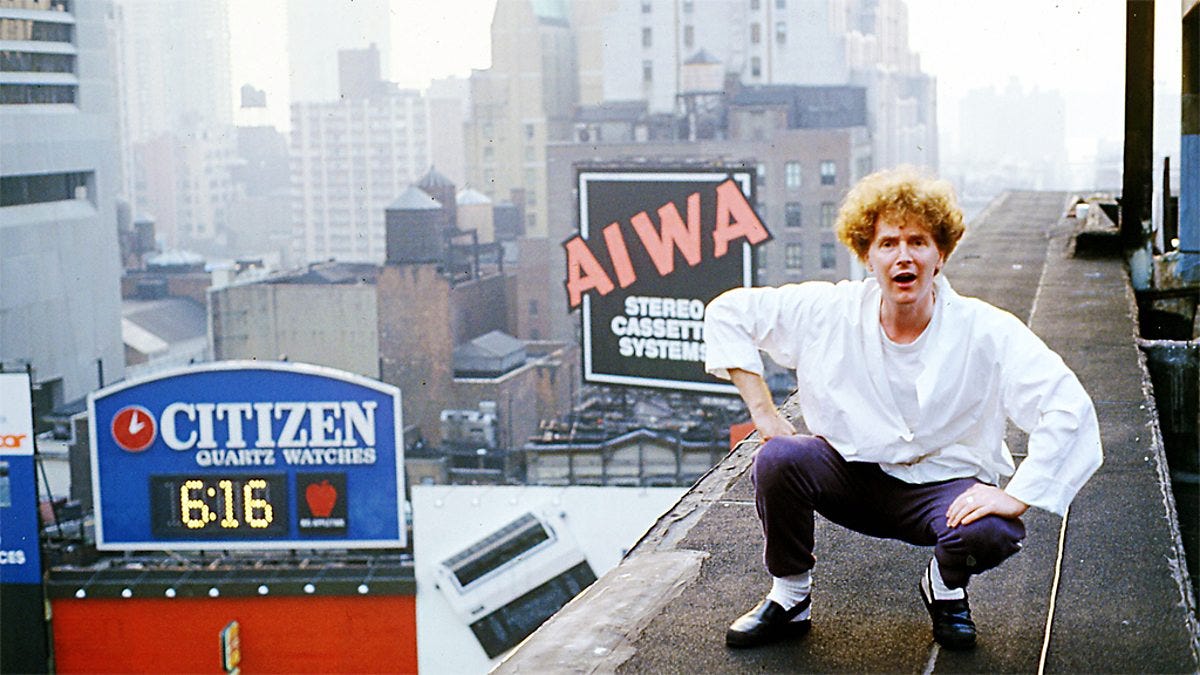

To understand where this new form of Musique Concréte originated from, and how it changed so many aspects of popular music, we must first start, like many things did back then, with Malcolm McLaren. In 1982, Malcolm commissioned Trevor Horn to help him with his new musical project. Not content with creating and then destroying Punk, stealing the Ants from Adam, setting Mr Goddard on a hit-bound, Burundi/Pirate/Red Indian fusion-based trajectory and forming Bow Wow Wow with the aforementioned stolen Ants, fronted by a 15-year-old girl who’d get the Mary Whitehouse brigade hot under the collar with a risqué album cover based on a classic Manet, Malcolm wanted to reach further still into the uncharted waters of “world” music.

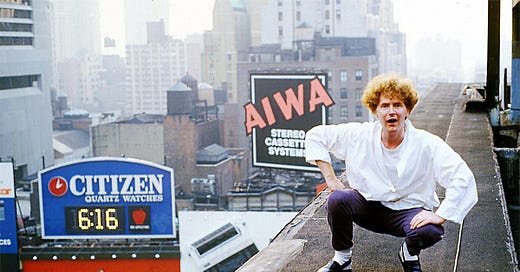

His vision for an album of songs that plagiarised, as was McLaren’s modus operandi, from musical cultures as yet unheard of to the average Western pop ear, was an ambitious one. It would involve numerous recording sessions with artists from Soweto to Tennessee via New York City. It would be fair to say he popularised world music some while before a certain Peter Gabriel did. But the story of Duck Rock is for another day. What we must take from this period in time is that Horn brought with him three vital members of his famous production team. Gary Langan was the engineer, JJ Jeczalik the Fairlight wizard and Anne Dudley was the classically trained musical genius. These three unassuming people, from Surrey, Oxfordshire and Kent respectively, corralled by their boss from Durham, would end up creating the beats and textures that would inform the beat makers of Hip Hop. And it all started with Duck Rock. Oh, and the Fairlight.

The Australian Fairlight Computer Musical Instrument was a machine that had been invented after a number of years of trying to come up with a digital synthesiser, based on Tony Furse’s QASAR additive synthesis instrument, that would accurately replicate acoustic instruments, which ultimately failed until one of its inventors, Peter Vogel, decided to “cheat” and digitally record the sounds he was trying to copy into electronic memory. Inadvertently, Peter had invented digital sampling and, when paired up with his other invention, the computer-based on-screen music sequencer known as Page-R, found that he now possessed a machine capable of accurately replicating real sounds and that allowed an individual user to create, compose and perform entire, multi-layered musical compositions without the need for anyone else to be involved.

Sampling, per sé, wasn’t new. The practice of recording audio and playing it back in a musical fashion had been going on for many years. But instead of turning sound into digital ones and zeros, musicians like Delia Derbyshire, Daphne Oram and Pierre Schaeffer had used magnetic tape, cut, looped and spliced to form other-worldly soundscapes, a practice commonly used by the BBC Radiophonic Workshop. Instruments like the Mellotron used loops of tape, each carrying a recording of an instrument at a particular pitch that was married up to a piano-style keyboard and that delivered authentic, albeit slightly ‘coloured’ representations of instruments like the flute, violin or brass section. The flutes, for example, at the beginning of The Beatles ‘Strawberry Fields Forever’ are Mellotron flutes. But tape-based sampling, which wasn’t called sampling back then, had many limitations. These were mainly physical but also artistic. Mellotron’s weighed a ton & tape loops created in the studio, such as those used by the BBC’s Radiophonic Workshop, sometimes stretched right around a studio’s control booth. Just ask 10CC how awkward those vocal “arhhhh” loops in “I’m Not In Love” were! And there was little you could do with the recorded sound besides shove the output through an effects unit. Digital sampling opened up a world of almost endless manipulation that had never been available before.

For a musical magpie like McLaren, you’d think the Fairlight would be a dream come true, but McLaren didn’t care about how his ideas were made, just that they were made. And so it was Trevor’s team that utilised this new technology to facilitate Malcolm’s vision. The knowledge gained on this album, and the impact the resulting songs had on popular culture all over the world, particularly in places like New York, led to much greater things.

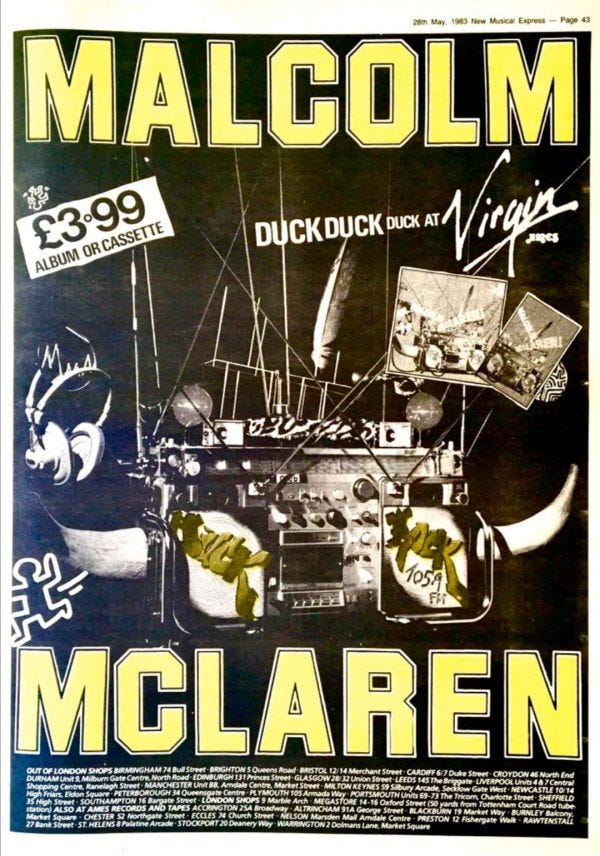

Trevor had, along with fellow Buggles member, Geoff Downes, briefly been a member of prog-gods Yes. After meeting him and Downes, who were, at the time, recording the sophomore Buggles album, via their mutual manager Brian Lane, Chris Squire and Steve Howe approached them to replace the recently departed Jon Anderson and Rick Wakeman. Being huge Yes fans, they accepted and embarked on the ‘Drama’ project. Yes’s die-hard Anderson fans immediately resented his replacement, despite Trevor actually doing a successful job filling his predecessor’s shoes. After the tour ended, Horn & Downes left and completed & released ‘Adventures in Modern Recording’ in late 1981. Eighteen months later, Yes approached Horn again to collaborate, this time requesting his production skills over his vocal ones. The result was ‘90125’, the album that broke Yes into mainstream pop/rock and one that a large amount of Fairlight was responsible for.

Yet again, Langan, Dudley and Jeczalik were part of Horn’s crew and it was during these sessions that Langan took some tapes that Horn had decided to discard and asked JJ to feed them into his Fairlight CMI IIx. The results blew their minds and they carried on sampling all kinds of sounds that they had captured in the preceding months, including the sound of JJ’s VW Golf Mk.1. ‘Cantata for VW Starter’ became ‘Beat Box’, and a chance playback to Trevor in his car one day had him heading to see Island Records owner, Chris Blackwell, who loved the tape so much, he took it to New York and played it out in a club. Blackwell, who was helping Trevor start up the ZTT label and who sold his studios on Basing St., London to Trevor (which later became SARM West but has since been redeveloped into luxury apartments), declared that Art of Noise should be their first signing. Enter, Paul Morley, stage right.

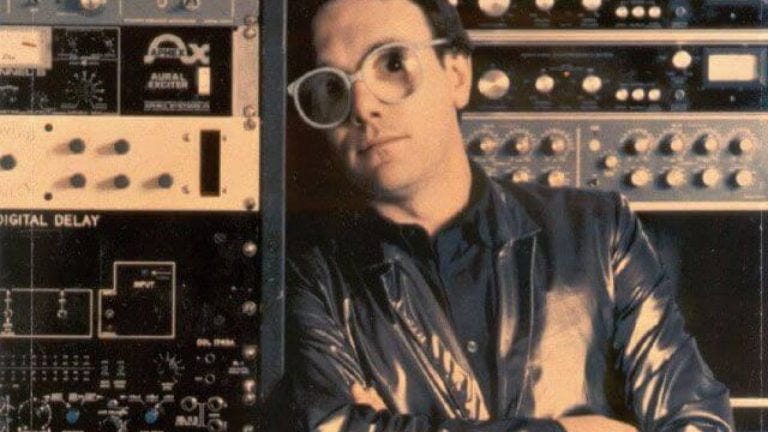

Morley had been the NME’s eyes and ears in Manchester for many years. A part of the music scene there for some while, he knew most of, if not all, the major protagonists. He was, famously, the individual who identified Ian Curtis’ body after his tragic demise. His wordy, contentious, pretentious, scathing yet passionate commentary on the Mancunian music scene that spearheaded Britain’s move out of the stinking cadaver of punk into the fresh, new meat that was New Wave, made him a love/hate character with purveyors and consumers of the music press alike. But in 1983, Morley found himself as the creative head of newly-formed label, ZTT (short for Zang Tumb Tumb or Zang Tuum Tumb or whatever alternate spelling Morley could come up with). Betraying his love for the Italian Futurist movement, ZTT was ruled by an (un)holy trinity of Morley, Horn and Horn’s wife, Jill Sinclair. Jill was the business brain, the tough-talking, no-bullshit negotiator and author of some legendary restrictive recording contracts. Just ask Holly Johnson. Horn was obviously the studio guru, or house producer, if you will. And Morley? Well, he did what he did best. Talk a lot about stuff he was passionate about, trying (and sometimes succeeding) to confound and educate us in equal measure. His vision for Art of Noise? A faceless, house band with a non-image.

So, ZTT was formed and Trevor & Paul went off to conquer the world whilst Jill attempted to rein them in financially for fear of following in the footsteps of Morley’s Mancunian hero, Mr Manchester himself, Anthony H Wilson. Factory Records were still going, thanks to New Order, but as history reminds us, it was more by luck than judgement.

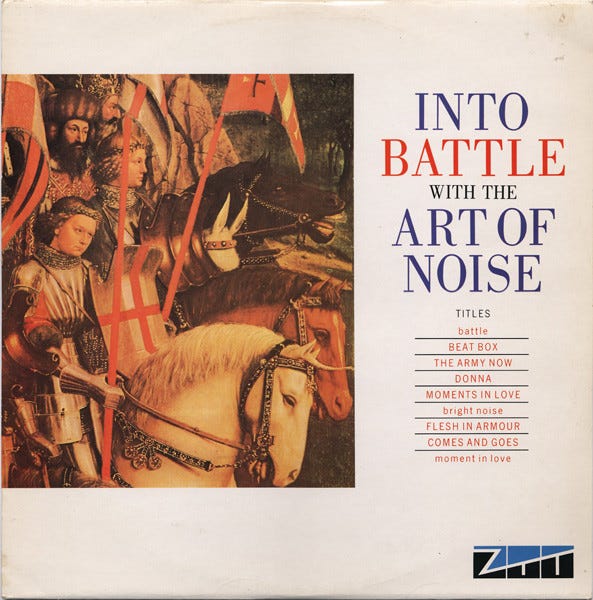

And so it was, that, as Chris Blackwell had suggested, the first ZTT release, Cat.No. ZTIS100, and its cassette counterpart, CTIS100, was released on the 26th September 1983. Entitled ‘Into Battle with the Art of Noise’, this EP from the ZTT house band consisted of two full songs, ‘Beat Box’ and the 10 minute epic, ‘Moments In Love’, surrounded by shorter snippets and segues, mostly created on the Fairlight. Its cover was a small piece (the bottom left part, to be precise) of the 1432 painting, ‘The Ghent Altarpiece’ by Hubert and Jan van Eyck, depicting Righteous Judges and Warriors of Christ. Visually striking, and an early indicator of how Morley, and XL Design (principle ZTT designers, headed up by Tom Watkins) would plagiarise and recycle imagery, just as Langan, Dudley and Jeczalik would recycle sounds. The sleeve layout was also a rip off of a Dave Brubeck Quartet sleeve for ‘Time Further Out’.

Into Battle’s two principle songs would make it onto the first Art of Noise long player, 1984’s ‘(Who’s Afraid of the) Art of Noise’ (ZTTIQ2) which would follow a year later. Between these two releases, Art of Noise released both ‘Beat Box’ and the now legendary ‘Close (to the edit)’, the latter bearing quite a resemblance to the former, and both released in many different edits, versions and mixes, across vinyl and cassette. Beat Box was often differentiated by its subtitle. For example Diversion One, Two, Six or Seven. Diversion Six, however, was also known as Diversion 10. This confusing proliferation of different versions was very much a Morley thing that he employed significantly during his tenure, causing the UK Charts company at the time to introduce rules to limit the contribution of multiple releases to a single’s chart position.

Decades later, this whimsical, yet quaint habit causes collectors like me an awful headache, particularly as Morley would send some obscure variation off to the pressing plant with the exact same catalogue number and sleeve as an earlier incarnation. It took me years to finally own all the different versions of Frankie Goes to Hollywood’s ‘Relax’ 12” single. And of course, Frankie were birthed out of ZTT’s loins shortly after Art of Noise’s debut, featuring contributions from all AoN members, and it would be they that dominated the charts for the following two years. However, one of the most remarkable things about Art of Noise was how such high-concept pop was adopted by the masses and achieved significant chart success of its own, as well as influencing the Hip Hop and Electro scenes at that time.

Looking back on it all, it seems a bit crazy. It is also incredibly enlightening. Here was a band, made up of men and women, on a label run by a woman and two men and delivering a brand of music and visuals that relied heavily on high-art influences and provocative conceptualisation, producing instrumental Musique Concreté and referencing Italian Futurists, Rimbaud and Faust in their sleeve notes. And yes, those sleeve notes were amazing. Aside from the snippets from philosophical tomes, there was subtle comedy and exquisitely clever marketing. I mean, what better way to encourage the purchaser of an album to explore the catalogue further and consume more product than to label your releases as part of a series. And not just number one in the series. Who’s Afraid was listed as, “…number 34 in Zang Tuum Tumb’s Incomplete Incidental Series (In its American sleeve it is number 16)”. The listener is instantly encouraged to find out what the other 33 instalments are, even if they don’t actually exist. It was conceited and incredibly successful. Morley had us all in the palm of his hand and we lapped it up.

And yet, despite all of this, Art of Noise and their work, either under their own name or via their behind-the-scene work with Yes, McLaren, Frankie and many more besides, are regularly cited by the innovators of musical movements such as Hip Hop, Industrial and Techno as key influences. The work they did with the Fairlight, alongside that of people such as Peter Gabriel, drove the art of sampling forward, forging new methods of sound design and pop music creation.

The start of noise continued with a bang as Frankie went on to rule the world, and ZTT finally, albeit far less disastrously, went the way of Factory. Proof that art and commerce are woeful bedfellows. After the initial success, Gary, Ann & JJ extricated themselves from ZTT, leaving Morley and Horn behind and went on to seek further chart success with, what some (i.e Morley) might call slightly more novelty recordings, such as their collaboration with Tom Jones on the Prince cover, ‘Kiss’ or their teaming up with the likes of Max Headroom and Duane Eddy on tracks such as ‘Paranoimia’ and ‘Peter Gunn’ respectively. AoN fell silent for a number of years in the 1990s but were resurrected at the turn of the century with Horn & Morley returning, Jeczalik & Langan departing and former 10CC legend, Lol Creme, joining. Their collective effort, AoN’s last album to date, ‘The Seduction of Claude Debussy’ saw a return to the more abstract ways of the past, embracing more contemporary musical styles such as drum ’n’ bass. Aside from a few compilations in recent years, Art of Noise currently remains dormant.

Suggested listening, viewing and reading:

http://artofztt.com

– Lovingly curated by ZTT fan, DJ and record collector, Kevin Foakes aka DJ Food.

http://www.zttaat.com/

– A vast, fan-made, collection of ZTT data, articles and imagery.

http://theartofnoiseonline.com/Home.php – The authorised AoN website, managed by Kevin Whitehouse.

https://www.discogs.com/Art-Of-Noise-And-What-Have-You-Done-With-My-Body-God/master/594437 – ‘And What Have You Done With My Body, God?’, a superb 4xCD box set charting the very early Art of Noise sessions, curated by former ZTT archivist, Ian Peel.

– A superb sonic essay by Daniel Haaksman on the creation of Malcolm McLaren’s ‘Duck Rock’ album.